It’s high summer, and island life is a-calling. Islands are reoccurring in literature - from Homer’s Ithaca, to the island living feral and misshapen Caliban, in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, all the way to, of course, Robinson Crusoe and Treasure Island. Perhaps because they exist with their own rules; ready to be bent, or conform to. Islands are ready to appear, and disappear - they sift into your imagination, and quietly con you into seeing things that might not be real. Or are they simply revealing the monsters and gods inside us? Islands offer a place where magic exists, and where we become sovereigns by sundown. They reveal who we are, think The Beach with Tilda Swinton, Blumhouse’s Fantasy Island or even, Jurassic Park.

What the island fantasy represents is a place for us to escape civilization, and to be able to isolate ourselves from our world - with the hope (I mean, barely a lick and a wish) to reflect on who we are…from a safer yonder. But you know what happens in HG Wells's The Island of Dr Moreau, and in The Lord of the Flies. Sometimes the island wins.

I once wrote a piece for Vogue about private islands - and visited them all, for research, naturally - and am always dreaming of having my own. I mean, how hard could it be to procure one?

I’ve ventured to more than 100 islands across the globe - from Greenland, to dozens of Greek pearls, all the way to Japan’s art island Naoshima and also ones with no names. Off Amanpulu, in the Cuyo Archipelago of northern Palawan in the Philippines, I’ve found myself alone on a shoal (let’s just call it a temporary sandy island) reflecting on my own fugaciousness. I am here now; to love, to live and to fuck it up - because the tide is always ready to come in. Sometimes wisdom can be so obvious, just too ready for you to blink and see it.

Listen to my podcast about another interesting island, hometown of Cristiano Ronaldo, Madeira.

The Caribbean Island You’ve Never Heard Of

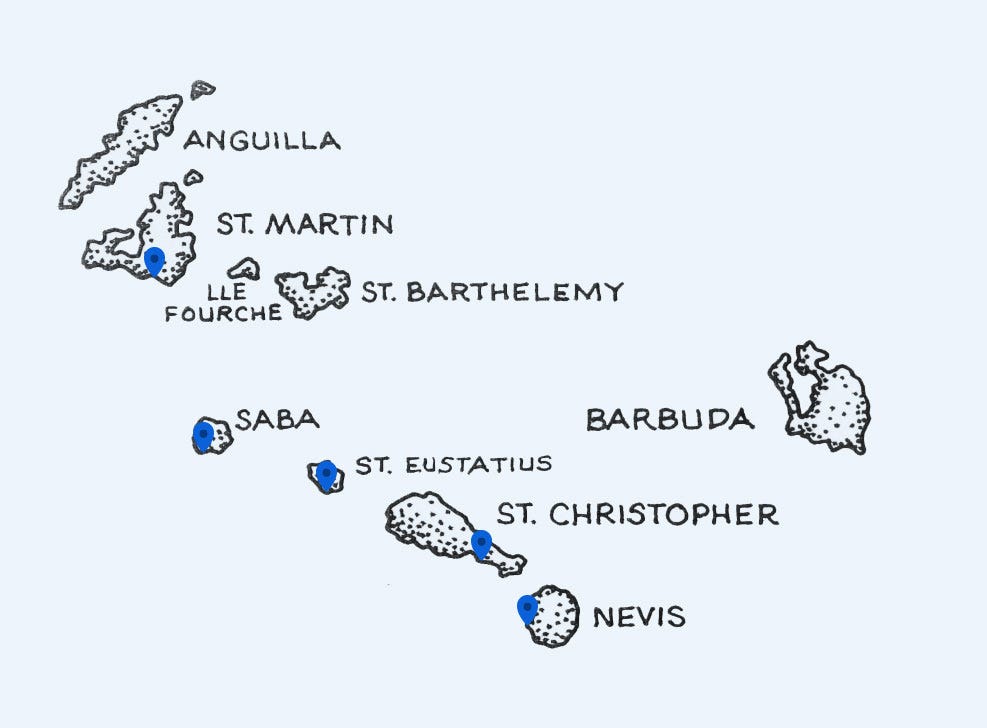

Maybe you’ve never heard of Saba before. But this tiny Caribbean island is purring, even setting up an Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion system to generate electricity and produce drinking water for the island. Pretty forward thinking for a five-square-mile island dubbed “rock” in Arawak Indian. Christopher Columbus supposedly sighted it in 1493 - and in fact, these very craggy shores are what deterred the explorer from alighting.

When the Spanish arrived around 1493, many of the island inhabitants were removed and taken as slaves to work in other parts of the Caribbean, which continued to happen until the 1800s with colonialism. Although evidence was found that Caribs and Arawak Indians inhabited the island, it was in 1635 that the French claimed the “unspoiled Queen” for King Louis XIII of France. Dutch settlers soon after populated there and it has been in their possession for roughly 355 years today.

The Netherlands’ smallest special municipality (officially called a “public body”) is just a 12-minute flight south of the more widely known Sint Maarten (also owned by the Dutch) and northwest of the increasingly popular Saint Kitts and Nevis. But thanks to a small airport, lack of a real harbor and sheer cliffs all around, it’s in no danger of being discovered any time soon.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not enticing for explorers looking to enjoy the Caribbean without all the traffic: Saba is basically a tropical forest island soaring 5,000 ft. from the sea floor. A potentially active volcano overlooks the red roofed cottages of its four major settlement towns, including the capital dubbed un-ironically “The Bottom.” White washed or stone exteriors, red zinc roofs, decorative Caribbean gingerbread trim and green shutters define Saba’s architecture—along with a law that dictates the island’s aesthetics.

Outside of the main towns and mountain villages most of the island’s 1,800 inhabitants call home, a forest paradise is filled with rare, tropical foliage. Wild orchids and donkeys occupy the island’s old stone paths and steps. These island paths were created by the island's residents before the vehicular roads were built, connecting pathways and steps made of the local volcanic rocks, as well as pathways crisscrossing the mountainside to the farmlands where the produce was then farmed.

If it all looks a little familiar, it’s with good reason. Saba’s silhouette was used in the original “King Kong” movie of the 1930s. At the beginning of the film, it serves as the backdrop for the colossal gorilla’s “Skull Island” home.

Hikers on the island can ascend to Mount Scenery, the island’s highest point, or take a more extreme North Coast hike that passes by old town ruins and culminates in ocean vistas. ‘Crocodile’ James Johnson, a multi-generational Saban - is the de facto ranger for all of Saba’s hiking trails, and he is a walking bush medicine and flora/fauna expert of the island. He says, “So, as I guide hikers to the top of Mt. Scenery, I like to share our lore and folk history with visitors. It is my way of keeping it alive, preserving it, along with all of the island's natural beauty.”

But the real attraction here is the scuba diving and snorkeling. An island with no beaches means fewer visitors - thus, the waters are clear and diving spots untainted. Divers find remarkable formations and structural diversity in the water, the legacy of the sea’s volcanic origins. From shallow patch reefs to deep-water seamounts, there is plenty of underwater action everywhere, and Hawksbill turtles, dolphins, lobsters, stingrays and bright tropical fish casually roll by. The island protects this infinite marine world with a self-sustaining marine park established in 1987. “Saba’s volcanic origins have bestowed the waters with spectacular formations and structural diversity, and we fiercely protect this natural beauty with the Saba Marine Park, one of the few self-sustaining marine parks worldwide, established to safeguard and ensure the continued quality of this extraordinary resource,” says Lynn Costenaro of the Sea Saba Dive Center.

But conservation and preservation is just part and parcel of the little island. The Saba Conservation Foundation, a non-profit non-government organization, was established in 1987 to protect the island’s natural and cultural heritage.

One of the island’s most famous colonial cultural traditions was also one of its most important industries. Intricate hand lace work was inherited from Spain by way of a nun from Venezuela in the 1880s, and the island’s craftspeople are experts. When regular mail service first connected the island to the outside world, the women of the island adapted their craft into a mail-order cottage industry, shipping everything from dresses to tablecloths to the U.S. Although the industry was once one of subsistence today it is more of a dying art with a younger generation encouraged to learn the craft to ensure its continuation.

Think of Saba as the low-key, more sustainable version of the Caribbean where polluting super yachts and mass resorts that harm the environment will hopefully never moor. Just don’t tell anyone.

The Atlantic’s Hidden Coffee Farm On The Azorean Island Of São Jorge

Somewhere in the middle of the nippy Atlantic Ocean, a quick little four-hour flight from Boston no less, is where the subtropical volcanic islands of the Azores truly hide out. Magical, mystical green lushness, oversized volcanic craters now reimagined as lakes, steaming natural hot springs that puff out from the earth, blue hydrangeas in the thousands, and more cows than humans - well, that’s the Azores for you. Aside from belonging to Portugal for most of their modern life - minus that Spanish moment in 1580 - the islands haven’t received their deserved love. Until now that is.

Aside from the nine islands that make up the archipelago, there are a few small towns with burgeoning dining scenes and some boutique hotels, hot springs, endless adventure activities (think horses, diving, kayaking) and, of course, one small island, São Jorge - with a marvelous coffee plantation. “The Azores has been waiting to be taken seriously as a perfect getaway destination—it has everything Europe has, but it’s just a little easier to navigate,” says Luis Nunes, whose family operates coffee farms (and a tourism company) on São Jorge. Just a quick hopper plane from the main island (where Ponta Delgado is the capital in case you’re wondering)—and you’ll arrive minutes later.

So what’s the big deal here? What makes these plantations so marvelous are the difficult to reach São Jorge fajãs. These are flat lands that are at sea level on the island and are very steep - a coffee bean’s dream haven. “These are results from the accumulation of debris, following earthquakes, or lava flows from volcanic eruptions, and their flat and fertile soils, create a very specific microclimate,” says Nunes.

“Unfortunately, there are no bibliographical references that accurately date the introduction of the coffee plantation in São Jorge,” says Dina Nunes, whose father Manuel is the farmer and owner of the small plantation as well as Cafe Nunes, its sister business. “However, there are some experts in the field who have likened the characteristics of the plants [Arabica coffee] to actually have come from Brazil.” Around the 17th and 18th century there was a strong emigration of Azoreans to Brazil - after the great earthquake of 1757 that shook, among other islands, the island of São Jorge.

“So in the late 18th-century transition to the 19th century possibly someone who worked on some coffee farm will have returned from Brazil to São Jorge, bringing coffee beans,” says Dina Nunes. In the ’90s, when the island had no tavern (or coffee shop for that matter), the craft shop located in the fajã brewed coffee to captivate the customers coming to buy the famous bedspreads made by the family. By 1997, they had set up a proper cafe.

São Jorge, the only coffee farm in Europe, says Dina Nunes, boasts “all the fundamentals for great coffee production.” Nunes explains that the plants grow at a super-low altitude with a climate that is in fact very similar to what Brazil has: “We are below 300 meters to almost sea level, with average annual temperatures ranging from 12 degrees Celsius in winter to 25 degrees Celsius in summer, plus a relatively average air humidity,” she explains.

The Nunes family bought the land almost 40 years ago - with only a small handful of plants. Today, they have 800 coffee plants and in the last year reached a final product of around 770 pounds of beans. “We exclusively have Arabica but we are totally biological - we do not require any chemicals to fight pests since they just do not exist here,” says Dina Nunes. “And we also fertilize with the husks, leaves, and the coffee grounds.”

The harvest season is between May and the end of August - the beans are all picked by hand and dried on a rack for three to four weeks. Nunes’s grandmother, Elvira Nunes, at age 92, is in charge of making sure all the impurities are removed from the beans. “The roasting is done the old-fashioned way: to the fire in an iron frying pan and stirring until desired color is obtained,” smiles Dina Nunes.

But as Manuel Nunes will tell you, he’s not interested in exporting. If you love coffee and are interested in his little piece of heaven, he suggests that you need to come see it for yourself to believe it. In the summer, he serves around 200 espressos per day. He is willing to sell you a small bag of beans. But first, sit down and enjoy that espresso.

Beautifully written Daniel! I want a bag of those beans!!! Haha!!

I vouch for Palawan, El Nido was mesmerizing.